What’s wrong with the inheritance? Let me illustrate it with an example.

Let’s say that a client asked you to create a traffic simulator application. He wants it to be able to simulate the movement of some vehicles. If you use an object oriented language like Ruby you’ll probably come up with a model class that contains all the logic and properties, like this:

Vehicle class

Vehicle class

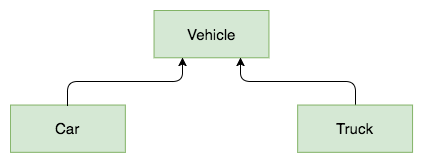

You reach back to the client with the complete solution. Fine. But now he tells you that he wants these vehicles to be either cars or trucks. You know these types will share at least some behavior, so you don’t want to duplicate the code. No problem! Let’s use inheritance! It’s a proper is-a relation, so why not?

Vehicle with inheritance

Vehicle with inheritance

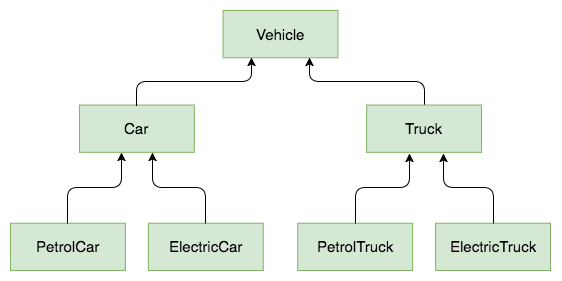

The client is happy again. But then he gets back to you and says that it would be great if these cars and trucks could have different types of engines. Let’s say: petrol or electric ones. Again, inheritance to the rescue!

Vehicle with even more inheritance

Vehicle with even more inheritance

The client is more than happy now. But what if he calls you back to ask for another fragmentation level? Say private cars, police cruisers, fire brigade trucks, ambulances and so on or and so forth? Our inheritance tree will grow bigger and become more complicated. Instead of reducing code duplication, we’ll end up with having the same logic in many places. There is even a wikipedia article describing this phenomenon.

This is not an artificial problem that I’ve just made up. I encountered it many times during my professional career either developing a new feature or trying to add a new behavior to a legacy code. It’s even more likely to happen when you use Rails which forces you to inherit from classes like ApplicationRecord or ApplicationController.

For the reference here is the code that may be produced with inheritance:

class Vehicle

def run

refill

load

end

end

class Car < Vehicle

def load

# load passengers

end

end

class Truck < Vehicle

def load

# load cargo

end

end

class PetrolCar < Car

def refill

# refill with fuel

end

end

class ElectricCar < Car

def refill

# refill with electricity

end

end

class PetrolTruck < Truck

def refill

# refill with fuel (code duplication!)

end

end

class ElectricTruck < Truck

def refill

# refill with electricity (code duplication!)

end

end

Can we do something about it? Yes, we can.

Maybe mixins?

Mixins are usually the first thing that comes to the minds of Ruby programmers when they notice that the inheritance is not a solution anymore. What are they? Basically they are modules with a set of methods that can be included into a class and become undistinguishable part of it. We can simply use them to extract any common logic and avoid code duplication.

Let’s see what we can do with the mixins. First, we need to create the modules that we’ll include later on:

module Vehicle

def run

refill

load

end

end

module Truck

def load

# load cargo

end

end

module Car

def load

# load passengers

end

end

module ElectricEngine

def refill

# refill with electricity

end

end

module PetrolEngine

def refill

# refill with petrol

end

end

Then we can define specific classes and include the mixins, that we’ve just created:

class PetrolCar

include Vehicle

include Car

include PetrolEngine

end

class ElectricCar

include Vehicle

include Car

include ElectricEngine

end

class PetrolTruck

include Vehicle

include Truck

include PetrolEngine

end

class ElectricTruck

include Vehicle

include Truck

include ElectricEngine

end

It looks better: no code is duplicated, we can add a new level of specialization and easily build any type of vehicle. It’s also clear what features our vehicles have.

There are still some problems though. When you look at this class you’re not sure how the included behavior is used. A mixin adds a couple of new methods but it’s not immediately obvious what they are, how does the class interfere with them and how does it affect the execution flow. If by any chance two modules contain methods with the same name, you’re gonna run into problems - one module will silently use the method from the other one. In the same way a module can mess up the code in your own class.

Mixins are not bad and there are definitely some good use cases for them. In my opinion they might work well when you want to define meta behavior of a class like logging, authorization or validation. The good thing is that they keep the code clean and small. They’re fine as long as you trust their implementation and know that they don’t break any other logic. The thing to remember is that in fact they’re just a way to implicitly implement multiple inheritance in Ruby.

In OOP there’s this thing to prefer composition over inheritance. And in Ruby people constantly forget that modules == multiple inheritance

— Piotr Solnica (@_solnic_) 20 lipca 2015

Can we do better? Yes, we can!

Composition

Composition is the term that I’ve known for a long time but started using it just recently. I simply didn’t feel it good enough to be able to use it comfortably. Then one day I came across an absolutely fantastic talk given by Sandi Metz in 2015 in Atlanta, called Nothing is something. Among other things she speaks about the composition and solves exactly the same problem that I mentioned in the beginning.

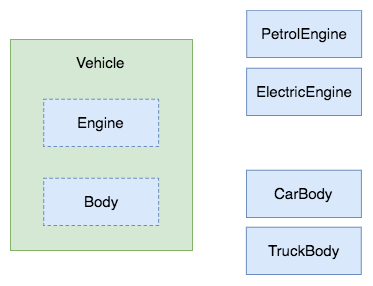

How does the composition work? Instead of trying to share the same behavior between classes, you should identify what kind of concepts are these things that differ, name them, extract into separate classes and then compose into your final object.

If inheritance is about is-a relationship, then composition is about has-a. Therefore we’ve got to change the structure of our problem in order to leverage the composition. Our vehicle is not an electric vehicle anymore but rather it has an electric engine. It is not a truck but it has a truck body. In that way we can identify two concepts: engine and body.

The structure of our application can now look like this. We have implemented the engine and body concepts and created two placeholders for them in the Vehicle class:

Composition in action

Composition in action

What does it look like in the code? Let’s start with the main class:

class Vehicle

def initialize(engine:, body:)

@engine = engine

@body = body

end

def run

@engine.refill

@body.load

end

end

Now we can create the implementations of our concepts. We will inject them into the Vehicle object.

class ElectricEngine

def refill

# refill with electricity

end

end

class PetrolEngine

def refill

# refill with petrol

end

end

class TruckBody

def load

# load cargo

end

end

class CarBody

def load

# load passengers

end

end

Finally, we can put everything together:

petrol_car = Vehicle.new(engine: PetrolEngine.new, body: CarBody.new)

electric_car = Vehicle.new(engine: ElectricEngine.new, body: CarBody.new)

petrol_truck = Vehicle.new(engine: PetrolEngine.new, body: TruckBody.new)

electric_truck = Vehicle.new(engine: ElectricEngine.new, body: TruckBody.new)

This approach has many advantages. The way that the vehicle classes use external logic is perfectly clear at the first glance. There are no problems with conflicting names either. Each class do exactly one thing (satisfying the single responsibility principle). Therefore you can easily test each of them by checking how well do they do this only thing.

We also achieved high cohesion (keeping the same logic together) maintaining low coupling (making classes loosely dependent on each other) at the same time. We can easily change the code responsible for engine or body not worrying about their clients, as long as we don’t change the interface.

Does composition have any downsides? Of course it does. It tends to make the code longer, especially when it comes to injecting all the dependencies into the final object. You have to write additional boilerplate in order to store references, setup delegations and enforce correct execution flow. As a remedy you can use one of many creational patterns, like Factory or Builder.

For me the hardest thing in composition was to change my mindset in order to be able to think about problems in that way. What unexpectedly helped me in this matter was playing with Go. It is a programming language that doesn’t have inheritance by design but makes it possible to write code in an object-oriented-like way. It also contains features which encourage programmers to use composition. Once I spent some time with it I suddenly realized that I became way more fluent in using this pattern. I’m going to describe it soon in the next blog post.

Conclusion

I gave you examples of three different approaches to structuring your code: inheritance, mixins and composition. Inheritance is the first choice for many programmers but to me it’s extremely overused, makes code complicated and hard to maintain. Mixins seem like a smart and more powerful replacement but in fact they are just a way to achieve implicit multi-base inheritance which can even increase code complexity. Composition is the most talkative but at the same time the most straightforward and clear approach to maintain dependencies between classes. It helps to keep them small, separated and easy to test. It’s my personal favorite.

You have to remember though that object-oriented programming is just a convention that some programmers came up with in order to help other programmers solve their problems. Don’t be a slave to these rules. Choose the solution that fits your situation best.

And after all, keep in mind that:

Designing object-oriented software is hard, and designing reusable object-oriented software is even harder. - Gang of Four

It comes with experience.