Go has been gaining a significant popularity over last few months. Language-related articles and blog posts are written every day. New Go projects are started on Github. Go conferences and meetups attract more and more people. This language certainly has its time now. It became a language of the year 2016 according to TIOBE and recently even made its way to their elite club of 10 most popular languages in the world.

I came across Go a year ago and decided to give it a try. After spending some time with it I can say that it’s definitely a language worth learning. Even if you’re not planning to use it in the long run, playing with it for a while may help you to improve your programming skills in general. In this post I’d like to tell you about five things that I’ve learned with Go and found useful in other languages.

1. It is possible to have both dynamic-like syntax and static safety

On a daily basis I work in Ruby and I really like its dynamic typing system. It makes the language easy to learn, easy to use and allows programmers to write code very quickly. In my opinion however it works very well mostly in a smaller codebase. When my project starts to grow and becomes more and more complicated I tend to miss the safety and reliability that statically typed languages provide. Even if I test my code carefully, it can always happen that I forget to cover some edge case and suddenly my object will appear in the context that I didn’t expect. Is it possible then to have a dynamic-like programming language and don’t give up the static safety at the same time? I think so. Let me speak in Go code!

Go is not an object-oriented language. There is an ongoing discussion whether Go is or is not an object-oriented language [1][2]. Even the authors don’t have a strong opinion [3]. But one of the OO features that Go definitely has is the interfaces. And they are pretty much the same as these you can find in Java or C++. They have names and define a set of function signatures:

type Animal interface {

Speak() string

}

Then we have Go’s equivalent of classes - structs. Structs are simple things that bundle together attributes:

type Dog struct {

name string

}

Now we can add a function to the struct:

func (d Dog) Speak() string {

return "Woof!"

}

It means that, from now, you can invoke that function on any instance of Dog struct.

This piece of code may seem strange at the first time. Why did we write it outside the struct? And what is this weird (d Dog) part before the function name? Let me explain. Authors of Go wanted to give users more flexibility by allowing them to add their logic to any type they like (as long as it is a part of the same package). Even to the ones they’re not authors of (like some external libraries). Therefore they decided to keep functions outside the structs. And because the compiler needs to know which type you’re extending, you have to specify its name explicitly and put it into this strange part called receiver.

To use the above code we can write a function that simply takes Animal as an argument and calls its method.

func SaySomething(a Animal) {

fmt.Println(a.Speak())

}

And as you can imagine we’re gonna put the Dog as an argument to the SaySomething function:

dog := Dog{name: "Charlie"}

SaySomething(dog)

“Very well”, you think, “but what do we need to do for the Dog to implement Animal interface?” Absolutely nothing, it’s done already! Go uses a concept called “automatic interface implementation”. A struct containing all methods defined in the interface automatically fulfills it. There is no implements keyword. Isn’t that cool? A friend of mine even likes to call it “a statically typed duck typing”, referring to the famous principle:

“If it quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck”.

Thanks to that feature and type inference that allows us to omit the type of a variable while defining, we can feel like we’re working in a dynamically typed language. But here we get the safety of a typed system too.

Why is this important? If your project is written in a dynamic, highly abstractive language one day you may find out that some parts of it need to be rewritten in a lower level, compiled language. I noticed however that it’s quite hard to convince Ruby or Python programmer to start writing in a static language and ask them to give up the flexibility they had. But it may be easier to do with “statically-duck-typed” Go.

2. It’s better to compose than inherit

In my previous blog post I described a problem that we can run into if we use object-oriented features too much. I told a story of a client that initially asks for a software that can be modeled with a single class and then gradually extends his concept, in a way that the inheritance seemed like a perfect answer for his increasing demands. Unfortunately, going that way led us to a huge tree of closely related classes where adding new logic, maintaining simplicity and avoiding code duplication was very hard.

My conclusion to that story was that if we want to mitigate the risk of getting lost inside the dark forest of code complexity we need to avoid inheritance and prefer composition instead. I know however that it can be hard to change your mind from one paradigm to another. In my case the thing that helped me the most was writing a code in a language that doesn’t support inheritance at all. You guessed it - that language was Go.

Go doesn’t have the concept of inheriting structs by design. The authors wanted to keep the language simple and clear. They didn’t find inheritance necessary, but they included a feature that is particularly useful when you want to use composition. In order to describe it, I’ll use an example taken from that other blog post.

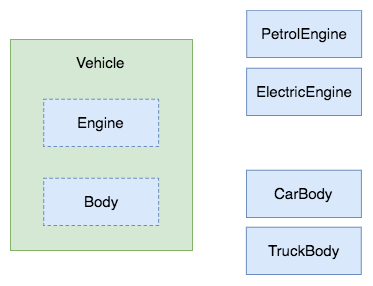

Let’s say that we’re modeling a vehicle that can have different types of engines and bodies:

Let’s create two interfaces representing these features:

type Engine interface {

Refill()

}

type Body interface {

Load()

}

Now we need to create a Vehicle struct that will compose above interfaces:

type Vehicle struct {

Engine

Body

}

Can you see anything strange here? I deliberately omitted names of the fields that these interfaces define. Therefore I used a feature called embedding. From now on every single method existing in the embedded interface will be also visible directly on the Vehicle struct itself. That means that we can invoke, let’s say, refill() function on any instance of Vehicle and Go will pass that through to the Engine implementation. We get a proper composition for free and we don’t need to add any explicit delegation boilerplate. That’s how it works in practice:

vehicle := Vehicle{Engine: PetrolEngine{}, Body: TruckBody{}}

vehicle.refill()

vehicle.load()

If you can’t switch your mind to prefer composition over inheritance in your object-oriented language - try Go and write something more complex than “hello world”. Because it doesn’t support inheritance at all, you’re gonna need to learn how to compose. Quickly.

3. Channels and goroutines are powerful way to solve problems involving concurrency

Go has some really simple and cool tools that help you work with concurrency: channels and goroutines. What are they?

Goroutines are Go’s “green threads”. As you can imagine, they are not handled by an operating system, but by the Go scheduler that is included into each binary. And fortunately this scheduler is smart enough to automatically utilize all CPU cores. Goroutines are small and lightweight, therefore you can easily create many of them and get advanced parallelism for free.

Channel is a simple “pipe” you can use to connect goroutines together. You can take it, write something to one end and read it from the other end. It simply allows goroutines to communicate with each other in an asynchronous way.

Here is a quick example of how they can work together. Let’s imagine that we’ve got a function that runs a long computation and we don’t want it to block the whole program. This is what can be done:

func HeavyComputation(ch chan int32) {

// long, serious math stuff

ch <- result

}

As you can see, this function takes a channel in its list of arguments. Once it obtains a result it pushes the computed value directly to that channel.

Now let’s see how we can use it. First we need to create a new channel of type int32:

ch := make(chan int32)

Then we can call our heavy function:

go HeavyComputation(ch)

Here comes a bit of magic - the go keyword. You can put it in front of any function call. Go will then create a new goroutine with the same address space and use it to run the function. All of these happen in the background, so the execution will return immediately to allow you to do other things.

And that’s exactly what’s gonna happen in this case. The just created goroutine will live asynchronously doing its job and then it’ll send the result to the channel once ready. We can try to obtain the result in the following way:

result := <-ch

If the result is ready, we’ll get it immediately. Otherwise we’d block here until HeavyComputation finishes and writes back to the channel.

Goroutines and channels are simple, yet very powerful mechanisms to work with concurrency and parallelism. Once you learn it, you’ll get a fresh look on how to solve this kind of problems. They offer an approach that is similar to the actor model known from languages and frameworks like Erlang and Akka, but I think they give more flexibility.

Programmers of other languages seem to start noticing their advantages. For instance, the authors of concurrent-ruby library, an unopinionated concurrency tools framework, ported Go’s channels directly to their project.

With that knowledge we can jump directly to the next paragraph.

4. Don’t communicate by sharing memory, share memory by communicating.

Traditional programming languages with their standard libraries (like C++, Java, Ruby or Python) encourage users to tackle concurrency problems in a way that many threads should have access to the same shared memory. In order to synchronize them and avoid simultaneous access programmers use locks. Locks prevent two thread from accessing a shared resource at the same time.

An example of this concept in Ruby may look like this:

lock = Mutex.new

a = Thread.new {

lock.synchronize {

# access shared resource

}

}

b = Thread.new {

lock.synchronize {

# access shared resource

}

}

Thanks to goroutines and channels Go programmers can take a different approach. Instead of using locks to control access to a shared resource, they can simply use channels to pass around its pointer. Then only a goroutine that holds the pointer can use it and make modifications to the shared structure.

There is a great explanation in Go’s documentation that helped me to understand this mechanism:

One way to think about this model is to consider a typical single-threaded program running on one CPU. It has no need for synchronization primitives. Now run another such instance; it too needs no synchronization. Now let those two communicate; if the communication is the synchronizer, there’s still no need for other synchronization.

This is definitely not a new idea, but somehow to many people a lock is still the default solution for any concurrency problem. Of course it doesn’t mean that locking is useless. It can be used to implement simple things, like an atomic counter. But for higher level abstractions it’s good to consider different techniques, like the one that authors of Go suggest.

5. There is nothing exceptional in exceptions

Programming languages that handle errors in a form of exceptions encourage users to think about them in a certain way. They are called “exceptions”, so there must happen something exceptional, extraordinary and uncommon for the “exception” to be triggered, right? Maybe I shouldn’t care too much about it? Maybe I can just pretend it won’t happen?

Go is different, because it doesn’t have the concept of exceptions by design. It might look like a lack of feature is called a feature, but it actually makes sense if you think about it for a while. In fact there is nothing exceptional in exceptions. They are usually just one of possible return values from a function. IO error during socket communication? It’s a network so we need to be prepared. No space left on device? It happens, nobody has unlimited hard drive. Database record not found? Well, doesn’t sound like something impossible.

If errors are merely return values why should we treat them differently? We shouldn’t. Here is how they are handled in Go. Let’s try to open a file:

f, err := os.Open("filename.ext")

As you can see, this (and many other) Go functions returns two values - the handler and the error. The whole safety checking is as simple as comparing the error to nil. When the file is successfully opened we receive the handler, but the error is set to nil. Otherwise we can find the error struct there.

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return err

}

// do something with the file

To be honest I’m not sure if this is the most beautiful way of handling errors I’ve ever seen, but it definitely does a good job in encouraging programmer not to ignore them. You can’t simply omit assigning the second return value. In case you do, Go will complain:

multiple-value os.Open() in single-value context

Go will also force you to read it later at least once. Otherwise you’ll get another error:

err declared and not used

Regardless of the language that you use on the daily basis it’s good to think about exceptions like they were regular return values. Don’t pretend that they just won’t occur. Bad things happen usually in the least expected moment. Don’t leave you catch blocks empty.

Conclusion

Go is an interesting language that presents a different approach to writing code. It deliberately misses some features that we know from other languages, like inheritance or exceptions. Instead it encourages users to tackle problems with its own toolset. Therefore, if you want to write maintainable, clean and robust code, you have to start thinking in a different, Go-like way. This is however a good thing, since the skills that you learn here can be successfully used in other languages. Your milage may vary, but I think that once you start playing with Go you’ll quickly find out that it actually helps you becoming a better programmer in general.